뉴욕타임즈, 한국 교육과정이 아동학대 초래

진보 교육감 대거 당선 긍정적 신호

뉴욕타임즈, 한국 교육과정이 아동학대 초래진보 교육감 대거 당선 긍정적 신호

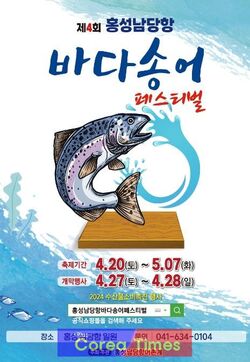

국정원 및 국가기관의 부정선거 개입으로부터 촉발된 외신들의 이러한 의구심은 세월초 참사에서 절정을 이루며 한국에 대한 비판적 기사들로 연일 외신을 장식하고 있다. 특히 이번 세월호 참사로 한국의 교육제도도 재조명을 받고 있다. 뉴욕타임스는 2일 전 예일대 한국학 연구원 강사이자 이달 말 출범할 뉴스웹사이트 코리아 엑스포제의 편집장인 구세웅씨의 한국 교육의 문제점을 들여다보는 장문의 기고문을 게재했다. ‘An Assault Upon Our Children-우리 아이들에 대한 폭행. South Korea’s Education System Hurts Students-한국 교육제도가 학생들을 해치고 있다‘라는 제목의 이 기사는 심하게 비뚤어진 한국 교육의 현 모습을 모든 과정이 아동학대를 초래하고 있다며 이 교육제도는 신속하게 개혁되고 재구성 되어야 한다고 지적하고 있다. 본인 스스로가 성공에 대한 심한 압력으로부터 보호하기 위한 어머니의 결정으로 캐나다로 조기유학을 떠났다고 밝힌 구씨는 어머니가 해외유학을 보낼 능력이 있었던 것은 행운이었다고 돌아보며 이야기를 풀어나가고 있다. 본인이 서울의 비싼 입시학원에서 11세의 아이들을 상대로 고급영문법을 가르친 경험이 있다고 밝힌 구씨는 학생들이 학업에는 진지했지만 죽은 눈빛이었다고 회상하며 이러한 환경이 행복하느냐는 질문에 ‘자기 학업 성취에 대해서 잔소리할 줄만 아는 자기 엄마가 죽으면 행복할 것 같다’는 한 소녀의 충격적인 대답을 소개한다. 이어 한국 교육은 기대 이상의 성과를 보이는 학생들을 많이 배출하고 있지만 학생들의 건강과 행복을 그에 대한 높은 대가로 지불한다고 문제점을 지적한 구씨는 이 모든 과정이 아동학대를 초래하고 있으며 이 교육제도는 신속히 개혁되고 재구성되어야 한다고 주장하고 있다. 국제평가에서 학생들이 학교에서 느끼는 만족도는 학업성과의 순위와 뒤바뀐다고 지적한 구씨는 겨우 60%의 학생들만이 학교생활에 만족하고 있다고 한국 학교생활의 현주소를 지적했다. 한국 교육에 대한 이 같은 현상에 대해 조선시대의 과거제도로 그 근원을 찾아간 구씨는 한국문화가 가족단위에 초점을 맞추고 있는 것이 주된 요소로 많은 부모들은 자녀들의 미래를 결정할 자신들의 권리를 신성불가침이라 여기고 있다고 한국 부모들의 과잉 교육열의 배경을 설명하고 있다. 구씨는 가족을 경제적으로 보는 시각 때문에 심지어 결혼조차 두 가족들 간의 경제적 거래의 역할을 한다며 궁극적으로 한국에서의 자녀가 된다는 것은 자유, 개인의 결정, 혹은 개인의 행복이 중요한 것이 아니고, 생산, 성취 그리고 복종이 중요하다고 설명했다. 구씨는 지난 6월 진보성향의 교육감들이 대거 당선된 것은 긍정적인 시도라며 개혁에 대해 점점 증가하는 국민들의 열망에 의해 이루어졌다고 평가하며 교육에서 어떤 의미 있는 변화를 가져오기 위해서는 아이들이 가정, 또는 국가 경제에서 상품처럼 취급되어 왔던 문화가 근본적으로 바뀌어야만 한다고 권유했다. 이어 구씨는 미쳐 날뛰는 사교육 산업은 아이들의 행복을 우선으로 놓기 위해 규제해야 된다며 과도한 사교육을 범죄로 간주하는 법률이 통과되면 이러한 악습에 대한 대항이 훨씬 더 효과적일 수 있다고 강력하게 사교육을 통제해야 한다고 주장했다. 한국의 부모들은 현 제도가 자기 자녀들의 행복에 대한 직접적인 폭력으로 작용함을 절대 인식하지 못할지도 모른다고 본 구씨는 학업의 성공이 인생의 최고라는 신념이 완전히 버려져야하며 한국이 선망의 대상이 되는 경제적 초강대국이 되었을지는 모르지만 국민의 행복은 무시해왔다고 지적했다. 구씨는 한국이 21세기의 모범으로 생각되어지기 전에, 교육으로 이어지는 오래된 봉건주의에 종지부를 찍어야하며 국가의 가장 힘 없는 국민들이 무엇을 원하는지에 대해 심사숙고해야 한다고 권유했다. 이번 뉴욕타임스의 이 기사는 숨진 세월호 학생들을 다시 한 번 떠올리게 한다. 제대로 피어나지도 못하고, 마음껏 놀아보지도 못한 아이들, 심한 교육에 대한 압박 속에서 겨우 맞은 설레는 수학여행 길에 어른들의 탐욕과 국가의 무능으로 차가운 물속에 수장되어 버린 아이들에게 행복을 위해 이 사회와 국가가 무엇을 했느냐는 질문을 새삼 던지게 된다. 구씨의 기고문에 나오는 ‘권위에 복종하는 것은 가정과 학교 모두에서 권장되는 사항’이라는 지적처럼 그러한 복종의 의무로 ‘가만히 있으라’는 명령에 그대로 학살당한 아이들. 구씨의 뉴욕타임스 기고문은 오늘 우리에게 많은 것들을 생각하게 한다. 다음은 <뉴스프로>가 번역한 구세웅씨의 뉴욕타임스 기고문 전문이다 번역 감수: 임옥 기사 바로가기☞ http://nyti.ms/1s5w6dq An Assault Upon Our Children 우리 아이들에 대한 폭행 South Korea’s Education System Hurts Students 한국 교육제도가 학생들을 해치고 있다  Photo Credit Andy Rementer SEOUL, South Korea — After my older brother fell ill from the stress of being a student in South Korea, my mother decided to move me from our home in Seoul to Vancouver for high school to spare me the intense pressure to succeed. She did not want me to suffer like my brother, who had a chest pain that doctors could not diagnose and an allergy so severe he needed to have shots at home. 한국, 서울 – 내 형이 한국의 학생으로서 받는 스트레스로 인해 병이 난 다음 어머니는 성공에 대한 심한 압력으로부터 보호하기 위해 나를 서울에서 벤쿠버로 유학보내 고등학교를 다니게 하기로 결정했다. 어머니는 의사도 진단을 내리지 못했던 가슴의 통증과 집에서 주사를 맞을 정도로 극심한 알레르기를 겪고 있던 내 형처럼 나도 고통 받기를 원치 않았다. I was fortunate that my mother recognized the problem and had the means to take me abroad. Most South Korean children’s parents are the main source of the unrelenting pressure put on students. 어머니가 문제를 파악했고, 또 나를 해외로 유학보낼 능력이 있었던 것은 내게는 행운이었다. 대개 한국 아이들의 부모들이야말로 학생들에 대한 혹독한 압력의 주요 장본인이다. Thirteen years later, in 2008, I taught advanced English grammar to 11-year-olds at an expensive cram school in the wealthy Seoul neighborhood of Gangnam. The students were serious about studying but their eyes appeared dead. 13년 후인 2008년 나는 서울의 부유한 동네인 강남의 비싼 입시학원에서 11세 아이들을 상대로 고급영문법을 가르쳤다. 학생들은 학업에 대해 진지했지만 이들의 눈빛은 죽은 듯 보였다. When I asked a class if they were happy in this environment, one girl hesitantly raised her hand to tell me that she would only be happy if her mother was gone because all her mother knew was how to nag about her academic performance. 이러한 환경에서 행복하냐고 수업 중 학생들에게 물었을 때, 한 소녀가 주저하듯 손을 들고 내게 말하기를 자기 학업 성취에 대해서 잔소리할 줄만 아는 자기 엄마가 죽으면 행복할 것 같다고 했다. The world may look to South Korea as a model for education — its students rank among the best on international education tests — but the system’s dark side casts a long shadow. Dominated by Tiger Moms, cram schools and highly authoritarian teachers, South Korean education produces ranks of overachieving students who pay a stiff price in health and happiness. The entire program amounts to child abuse. It should be reformed and restructured without delay. 세계가 한국을 교육의 모범사례로 볼지 모르지만 – 한국 학생들이 국제 교육 경시대회에서 최상위를 차지하기에 – 교육체제의 어두운 면이 긴 그림자를 드리우고 있다. 극성 엄마들과, 입시준비 학원, 그리고 극도로 권위적인 교사들이 지배하는 한국의 교육은 기대 이상의 성과를 보이는 많은 학생들을 배출하고 있지만, 학생들의 건강과 행복을 그에 대한 높은 대가로 지불한다. 이 모든 교육과정은 결국 아동학대를 초래하고 있다. 이 교육제도는 신속히 개혁되고 재구성돼야한다. Granted, the South Korean system has its strengths. The idea that success is most important, no matter the cost, is a great motivator. My report card after the first exam in middle school ranked me 21st out of 60 students in my homeroom class. My mother, who was enlightened about the extreme horrors of South Korean education but nevertheless worried about my grades, immediately found me a private tutor for math, which helped me shoot up to a respectable No. 3 in the homeroom hierarchy. 한국의 교육체계에 장점이 있는 것도 사실이다. 어떠한 대가를 치루더라도, 성공이 가장 중요하다는 생각은 동기부여를 확실히 해준다. 중학교 시절 첫 시험에서 내 성적표는 우리반 60명 중에서 21등이었다. 한국교육에 대한 극도의 공포에 대해 깨어 있었지만 그럼에도 불구하고 내 성적을 걱정한 어머니는 즉시 나에게 수학 개인교사를 구해 주었고, 그러자 내 학급석차는 부끄럽지 않은 3등으로 올라갔다. But that was the early 1990s. Since then, this culture of competition has only spread. 그러나 그 때는 1990년대 초반이었다. 그 후로 이 경쟁문화는 보다 확산됐을 뿐이다. Cram schools like the one I taught in — known as hagwons in Korean — are a mainstay of the South Korean education system and a symbol of parental yearning to see their children succeed at all costs. Hagwons are soulless facilities, with room after room divided by thin walls, lit by long fluorescent bulbs, and stuffed with students memorizing English vocabulary, Korean grammar rules and math formulas. Students typically stay after regular school hours until 10 p.m. or later. 내가 가르치고 있는 곳과 같은 입시학원 – 한국어로 학원으로 알려져 있는 -은 한국교육의 중심기둥이자 어떤 대가를 치르더라도 자녀들의 성공을 바라는 부모들의 갈망의 상징이다. 얇은 벽으로 나뉘어 있으며, 기다란 형광등으로 불을 밝히고, 영어 단어와 국문법규칙과 수학공식을 외우는 학생들로 꽉 찬 방으로 연달아 이뤄진 학원은 영혼 없는 시설이다. 학생들은 보통 방과 후 밤10시 또는 더 늦게까지 이곳에 머문다. Herded to various educational outlets and programs by parents, the average South Korean student works up to 13 hours a day, while the average high school student sleeps only 5.5 hours a night to ensure there is sufficient time for studying. Hagwons consume more than half of spending on private education. 부모가 이끄는대로 여러 교육장과 교육프로그램으로 끌려다니며, 한국 학생들의 평균 하루 공부시간은 13시간에 이르며, 고등학생의 평균 수면시간은 공부에 충분한 시간을 확보하기 위해 겨우 5.5시간에 불과하다. 사교육 소비에서 학원은 그 절반 이상을 차지한다. This “investment” in education is what has been used to explain South Koreans’ spectacular scores on the Program for International Student Assessment, increasingly the standard by which students from all over the world are compared to one another. But a system driven by overzealous parents and a leviathan private industry is unsustainable over the long run, especially given the physical and psychological costs that students are forced to bear. Many young South Koreans suffer physical symptoms of academic stress, like my brother did. In a typical case, one friend reported losing clumps of hair as she focused on her studies in high school; her hair regrew only when she entered college. 이런 교육에 대한 “투자”는 전 세계로의 학생들을 서로 비교하는 기준으로서 국제 학생평가프로그램에서 한국 학생들의 탁월한 성적을 설명하는 이유가 되어왔다. 그러나 지나치게 열정적인 부모들과 거대한 사적 산업에 의해 운영되어 온 시스템은 장기간에 걸쳐 유지될 수 있는 것이 아니며 학생들이 견디도록 강요 받는 육체적이고 정신적인 대가를 생각할 때 특히 그렇다. 많은 한국의 아이들은 내 형이 그랬던 것처럼 학업에 대한 스트레스가 가져오는 육체적인 고통을 받고 있다. 전형적인 사례로, 한 친구는 고등학교 학업에 집중하던 당시 머리카락이 뭉치로 빠졌고 대학에 들어가고 나서야 겨우 머리가 다시 자랐다고 말했다. Students are also inclined to see academic performance as their only source of validation and self-worth. Among young South Koreans who confessed to feeling suicidal in 2010, an alarming 53 percent identified inadequate academic performance as the main reason for such thoughts. Not surprisingly, South Korea’s position in the international education hierarchy is flipped when it comes to youth happiness, with only 60 percent of the country’s students confessing to being content in school, compared with an average of 80 percent, in 2012, among the world’s wealthy nations. There is a historical explanation for South Korea’s education fervor. During the Choson Dynasty (1392-1910), having children pass the civil service examination administered by the royal court was seen as a sure conduit to social and material success for the entire family. As the late Professor Edward Wagner at Harvard noted, even then a form of private education persisted, with candidates taking years of lessons to prepare for the exam and wealthier families splurging on special tutors. 학생들은 또한 학업성과만이 스스로에 대한 검증과 자긍심을 갖게 하는 유일한 근거라고 생각하는 경향이 있다. 2010년 자살을 생각했다고 고백한 한국의 젊은이들 중 놀랍게도 53퍼센트가 주된 이유가 학업성적 부진이라고 말했다. 국제 교육 평가의 서열에서 한국이 차지하는 위치는 학생들이 학교에서 느끼는 만족도에 대해 말할 때 뒤바뀌는 것도 놀라운 사실이 아니어서, 세계 부유국가들 중에서 만족도가 2012년도에 평균 80퍼센트인 것과 비교, 겨우 60퍼센트에 불과한 학생들이 학교에 만족하고 있다고 말했다. 한국의 교육열에는 역사적 배경이 있다. 1392년에서 1910년까지의 조선왕조 시절 왕실에서 집행하는 과거시험을 통과하는 자녀를 가지는 것이 온가족에게 사회적이고 물질적인 성공으로의 확실한 통로로 여겨졌다. 하버드의 고 에드워드 와그너 교수가 말했듯이, 당시에도 과거 응시생들이 과거를 준비하며 여러 해에 걸쳐 수업을 받고, 부유한 가정들은 특별 가정교사를 모시는 등 일종의 사교육이 존재했다. Korean culture’s special focus on the family unit is also a major factor. Many parents believe that their right to decide their children’s future is sacrosanct. And the view that the family is an economic unit perpetuates such tight control over children. Marriage, for example, still often functions as a financial transaction between two families. To be a South Korean child ultimately is not about freedom, personal choice or happiness; it is about production, performance and obedience. 한국 문화가 가족 단위에 특별한 초점을 맞추고 있다는 것 또한 주된 요소이다. 많은 부모들은 자녀들의 미래를 결정할 자신들의 권리를 신성불가침이라 여긴다. 그리고 가족을 경제적 단위로 보는 시각 때문에 자녀들에 대한 그런 엄한 규제가 지속된다. 예를 들어, 결혼은 여전히 종종 두 가족들 간의 경제적 거래로서의 역할을 한다. 궁극적으로 한국에서의 자녀가 된다는 것은 자유, 개인의 결정, 혹은 개인의 행복이 중요한 것이 아니고, 생산, 성취 그리고 복종이 중요해진다. Obedience to authority is enforced both at home and school. I remember the time I disagreed with my homeroom teacher in middle school by writing him a letter about one of his rules. The letter led to my being summoned to the teacher’s office, where I was berated for an hour and a half, not about the substance of my words but the fact that I had expressed my view at all. He had a class to teach but he did not bother to leave our meeting because he was so enraged that someone had questioned his authority. I knew then that trying to be rational or outspoken in school was pointless. 권위에 복종하는 것은 가정과 학교 모두에서 권장되는 사항이다. 중학교 시절 담임선생님에게 그의 규칙 중 하나에 대해 편지를 써서 선생님과 동의하지 않았던 기억이 있다. 그 편지 때문에 나는 교무실로 불려가 한 시간 반 동안 호되게 꾸중을 들었는데, 그것은 내가 한 말의 내용이 아니라 내 의견을 표출했다는 사실 때문이었다. 누군가가 자신의 권위에 도전한 것에 격분했기 때문에, 그는 수업이 있었지만 그 자리를 뜨지 못했다. 학교에서 합리적, 혹은 내 의견을 말하는 것이 무의미하다는 걸 나는 그 때 알았다. Despite decades of outright abuse and the entrenchment of this disturbing system, signs are emerging that some people are beginning to take reform seriously. In the course of coming to terms with the legacy of dictatorial rule, South Koreans have embraced the notion of “healing,” with the understanding that past political repression and continuing social pressure have engendered psychological ills that require redress. That trend has led to discussion of the detrimental effects the education system has on students and what should be done. 수십년에 걸쳐 이 좋지않은 제도의 공공연한 악용과 확립에도 불구하고, 일부 사람들이 변혁을 심각하게 받아들이기 시작했다는 신호들이 나타나고 있다. 독재정권의 유산이 끝을 보는 것과 함께 해서, 한국인들은 과거 정치적 억압과 지속된 사회적 압박이, 수정을 요하는 심리적 문제를 야기시켰음을 이해하며 “치유”라는 개념을 포용해 왔다. 그 흐름은 교육제도가 학생들에게 미친 악영향과 이에 대해 무엇을 해야하는지에 대한 토론을 이끌어 냈다. Another sign that things may move in a positive direction is the election in June of a large number of progressive education superintendents around the country, spurred by the growing desire of the public for reforms. But to effect any meaningful change in education, a culture that treats its children as a commodity to be used in the service of the family or the national economy must be radically altered. The government must halt its unrelenting pursuit of a higher birthrate in the face of a shrinking population and cease viewing children as mere cogs in the country’s economy with no right to personal happiness. South Korea must also encourage its citizens to see marriage not as a dutiful union that must yield tangible economic benefits, but as a life choice that can bring contentment and well-being. Only then can children be perceived as individuals with free will, rather than mere producers of wealth and status subject to onerous education. A private education industry run amok must be better regulated to put children’s welfare first. 긍정적인 방향으로 일들이 진행되고 있음을 보여주는 또 다른 신호는 6월 선거에서 전국적으로 많은 수의 진보적 성향의 교육감들이 당선된 것으로, 이것은 개혁에 대한 국민들의 점점 증가하는 열망에 의해 이루어진 것이다. 그러나 교육에서 어떤 의미 있는 변화를 가져오기 위해서는 아이들이 가정, 또는 국가 경제에서 상품처럼 취급되어 왔던 문화가 근본적으로 바뀌어야만 한다. 정부는 인구감소라는 상황 때문에 높은 출산율을 지나치게 추구하는 것을 중지해야 하고, 아이들을 개인의 행복에 대한 권리도 없는, 국가경제의 톱니바퀴에 지나지 않는 것으로 보는 것을 멈추어야만 한다. 국가는 또한 국민들이 결혼에 대해, 눈에 보이는 경제적인 이익을 산출해야만 하는 의무적인 결합이 아니라 만족과 행복을 가져올 수 있는 인생의 선택으로 보도록 해주어야 한다. 그래야만 아이들이 단지 과도한 교육의 결과인 부나 사회적 지위의 생산자들이 아니라 자유의지를 가진 개인들로 인식될 수 있다. 미쳐 날뛰는 사교육 산업은 아이들의 행복을 우선으로 놓기 위해 규제하는 편이 훨씬 나을 것이다. Although successive presidents have made attempts to rein in the cram schools, including mandating a 10 p.m. closure, many hagwon owners flout the regulations by operating out of residential buildings or blacking out windows so that light cannot be seen from outside. And some parents hire private tutors to get around the rule. 밤 10시 종료 지시를 포함해서, 역대 대통령들이 입시학원을 억제하기위한 노력을 해왔으나 많은 학원 소유주들이 주거건물 밖에서 운영하거나 창문을 막아 빛이 외부에서 보이지않게 하는 방법으로 규정을 무시한다. 그리고 일부 학부모들은 이 규칙을 피해가기 위해서 가정교사를 채용한다. The fight against these abuses would be far more effective if legislation were passed criminalizing excessive private education. Otherwise, South Korean parents may never recognize that the current system is a direct assault on the welfare of their own offspring. But above all, the conviction that academic success is paramount in life needs to be set aside completely. South Korea may have become an enviable economic superpower, but it has neglected the happiness of its people. 과도한 사교육을 범죄로 간주하는 법률이 통과되면 이러한 악습에 대한 대항이 훨씬 더 효과적일 수 있다. 그렇지 않으면, 한국의 부모들은 현 제도가 자기 자녀들의 행복에 대한 직접적인 폭력으로 작용함을 절대 인식하지 못할지도 모른다. 그러나 무엇보다도 학업의 성공이 인생의 최고라는 신념이 완전히 버려져야한다. 한국이 선망의 대상이 되는 경제적 초강대국이 되었을 지는 모르지만 국민의 행복은 무시해왔다. Decrying the state of young people’s existence in Korea, Yi Kwang-su, an early reformist intellectual, wrote in a 1918 essay, “On Child-Centrism,” “As long as parents live, children have no freedom and are treated like slaves or livestock not unlike subjects of a feudal lord.” Before South Korea can be seen as a model for the 21st century, it must end this age-old feudal system that passes for education and reflect on what the country’s most vulnerable citizens might themselves want. 한국의 젊은이들의 상태를 비난하면서, 초기 개혁론자 학자 이광수는 1918년 논문 “자녀중심론”에 이렇게 쓰고 있다: “부모가 살아있는동안 자녀는 자유가 없으며 영주의 신민이나 다름없는 노예나 가축처럼 취급을 받는다.” 한국이 21세기의 모범으로 생각되어지기 전에, 교육으로 이어지는 오래된 봉건주의에 종지부를 찍어야하며 국가의 가장 힘 없는 국민들이 무엇을 원하는지에 대해 심사숙고해야 한다. Se-Woong Koo, a former fellow and lecturer in Korean studies at Yale, is the editor in chief of Korea Exposé, a news website launching later this month. 구세웅은 전직 예일대학교 한국학 연구원이자 강사이며, 이 달 말 출범할 뉴스웹사이트 코리아 엑스포제의 편집장이다. <저작권자 ⓒ pluskorea 무단전재 및 재배포 금지>

교육 관련기사목록

|

연재

많이 본 기사

|

'잊혀진 계절'누굴위해 존재하는가

'잊혀진 계절'누굴위해 존재하는가